A Prince in his prime: Kumar Shri Ranjitsinhji - cricket's first global superstar

Kumar Shri Ranjitsinhji was cricket’s first global superstar. During cricket’s Golden Age at the end of the 19th century ‘Ranji’ was arguably the most talented and certainly the most exotic cricketer in a period of brilliantly accomplished and flamboyant players.

His peers – Sussex team-mate CB Fry, Gilbert Jessop and even the great WG Grace – acknowledged it and so did his adoring public, both in his adopted county and beyond at a time when Test and county cricket was firmly establishing itself in the nation’s consciousness thanks to the growth of the popular press.

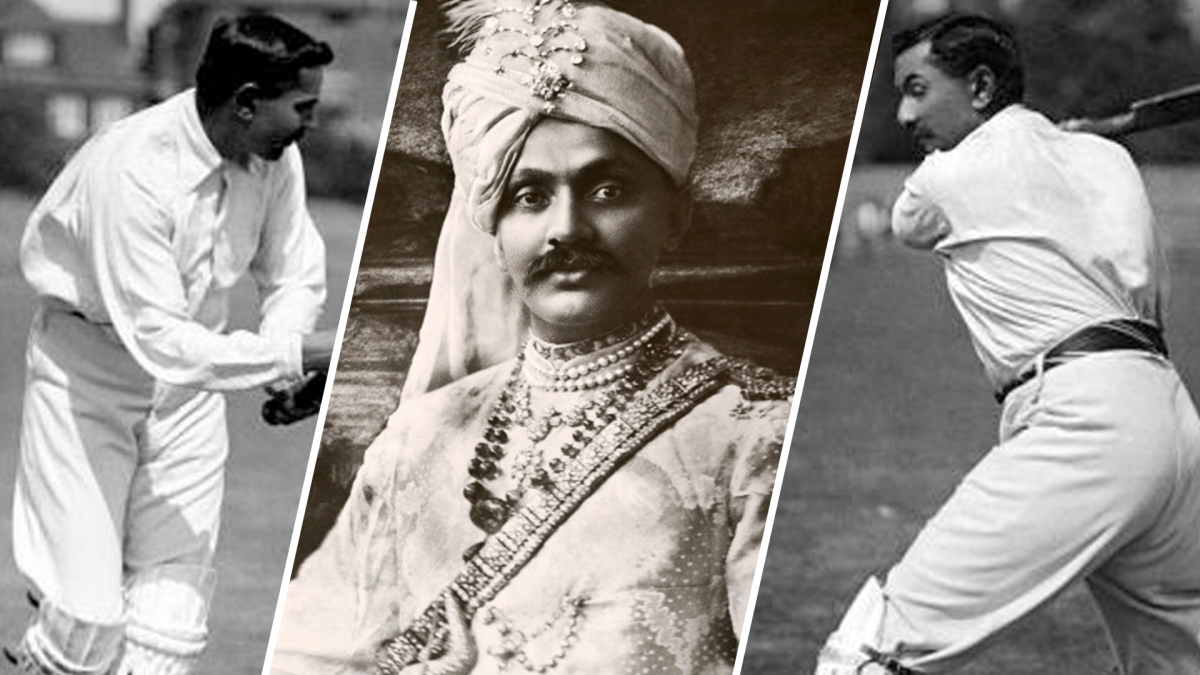

Ranji was more than just a fine cricketer, credited with the invention of the late cut and leg glance. But how could you compare him with the current generation of players? Well, think of a player with the wristy skills and dexterity of Sachin Tendulkar with the peacock’s showmanship of a Kevin Pietersen. Even then you don’t come close to describing a player of his extraordinary gifts.

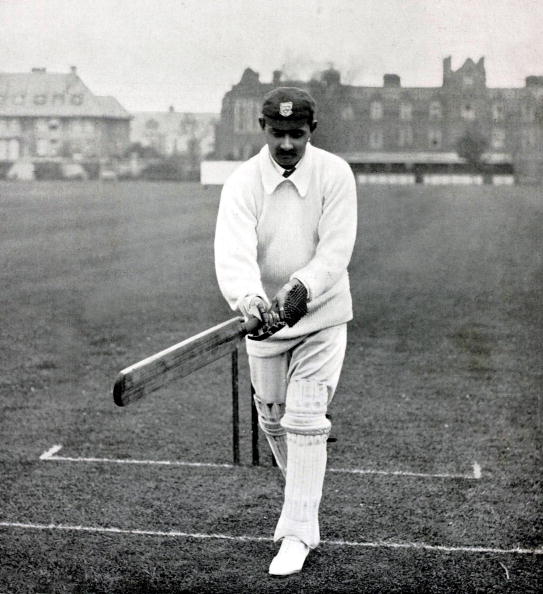

Ranjitsinhji plays his famous leg glance shot at Hove

“From the moment he stepped out of the pavilion he drew all eyes and held them,” wrote Jessop in the 1920s. “No one who ever saw him bat will forget it. He was the first man I know who wore silk shirts, and there was something very romantic about the very flow of his sleeves and the curve of his shoulders.

"He drew the crowds wherever he went, and at the height of his cricket days the shops in Brighton would empty if he passed along the street. Everyone wanted to see him. Whenever I bowled against him I felt he was impregnable. My impression was ‘I will never get this man out’. He was indisputably the greatest genius cricket has ever produced.”

A century and more on some might question the validity of Jessop’s statement but at the turn of the 20th century Ranji became the first sportsman, and certainly the first non-white sportsman, in the world to gain renown and respect beyond the boundaries of the game they played, although the MCC had serious misgivings in the build-up to his Test debut in 1896 against Australia – eight years after he had arrived from India to study at Cambridge – on the grounds of his colour.

Sussex historian Home Gordon wrote: “Old gentlemen waxing plethoric declared that if England could not win without resorting to the assistance of Asiatic extraction it had better devote its skill to marbles. One MCC veteran told me that if it were possible he would have expelled me from the club for having the disgusting degeneracy to praise a dirty black.”

Scores of 62 and 154 not out at Old Trafford on his England debut in 1896 only partially placated his critics.

The MCC had little choice but to select him. His achievements at the time were known not only to cricket followers but to those who took merely a passing interest in the game. In 1896 he scored 2,780 runs – a new record – including ten centuries. In 1899 he made 3,159 runs and 3,065 the following year which included five double-centuries, an astonishing performance given that no one had scored more than two in a season up until then.

And at the height of his powers Ranji achieved something that has never happened again in the history of the game – against eventual county champions Yorkshire in August 1896 he scored two hundreds in the same day.

Born in 1872, he had been brought to England in 1888 by the principal of his Indian college to study at Trinity College, Cambridge. It soon became apparent that he had little regard for academic studies, preferring instead to play games. As well as cricket, he was a superb racquets player thanks to his astonishingly powerful eyesight.

“I played often with him and against him and it seemed his eye was infallible,” wrote Jessop. "He could judge the length or flight of the ball so quickly that he had time then to decide which shot to play.”

Ranji had played cricket in India but it was while watching Australia’s CTB Turner take a hundred off the Surrey attack at the Oval during that first summer in England in 1888 that he decided to devote his energies to the game. He was a magnificent batsman with so many natural gifts but he practiced assiduously when the Surrey professionals went to work with the Cambridge students to hone his talent.

It was around this time that he perfected the leg glance, initially by anchoring his right leg to the ground during practice. He would move his left leg away from the ball towards the covers and discovered in doing so that he could turn or flick the ball behind his legs. The shot had probably been played before but not with the same effectiveness.

Ranji’s prolific run-scoring in games around Cambridge began to get him noticed and by 1895 he had become friendly with the amateurs in the Sussex team and in particular CB Fry, who was studying at Oxford and against whom he had occasionally played, as well as the county captain Billy Murdoch, who was keen for Ranji to play for Sussex as an amateur.

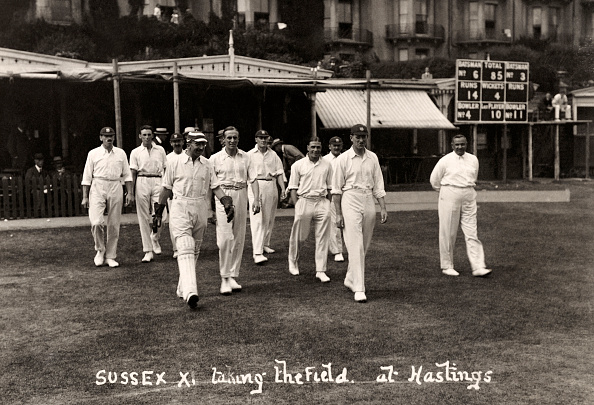

Ranjitsinhji (bottom left) and his Sussex teammates ahead of their match vs. Somerset at Hove on 26 May 1904

The club agreed to pay his hotel and out-of-pocket expenses and while there are no records of other ‘payments’ it is impossible to believe that someone with Ranji’s immeasurable box-office appeal would not have received some sort of sinecure on top.

At the time, to play for a first-class county a player had to have been resident for two years although it was difficult to establish whether rules were being bent or not. It was up to other counties to protest and when Ranji explained that he would be moving to Eastbourne there was little reaction. But, as the following year’s Wisden observed, ‘Ranji’s appearance for Sussex took most people by surprise, as the fact of him qualifying for Sussex was practically unknown until the early part of May 1895.’

His Sussex debut came against MCC at Lord’s. After taking a catch at slip to dismiss MCC captain Grace, he scored a fluent 77 not out of a total of 219 in Sussex’s first innings. Grace made a hundred in the second innings before he was caught off one of Ranji’s off-breaks.

He went on to take six wickets but before the close Sussex, set 405 to win, had lost a wicket and when the final day began there were fewer than 100 spectators in the ground. A Sussex defeat looked inevitable.

It was then that Sussex and English cricket at large discovered its new hero. Promoted to No.4, he made 112 in the pre-lunch session and by the afternoon scored 150 of the 208 runs Sussex scored in just over two and a half-hours.

When he was bowled by Grace he returned to the amateurs’ dressing room to prolonged applause from the MCC members, whose number had grown to several hundred as news of Ranji’s astonishing performance spread on the telegraph wires and in the early editions of the evening papers. He remains one of only seven Sussex batsman to score a century on their debut for the county, having previously played first-class cricket elsewhere.

MCC won the game by 19 runs but cricket had found itself a star and soon Ranji was winning admirers throughout England. That summer, as he appeared on grounds he had never played on for the first time, word of mouth ensured he would do so in front of big crowds. Even Grace, who at the age of 47 was enjoying a return to the form of his halcyon days, found his achievements completely overshadowed, despite scoring more runs (2346 at 51) compared to Ranji’s 1775 at 49.

The statistics, certainly as far as the sporting public were concerned, had become an irrelevance.

It wasn’t always easy for Ranji though. Five days after the MCC match he got so cold in the field at Trent Bridge he stopped the ball with his feet when it came near him and kept his hands in his pockets. When a sudden snow storm swept over the ground his team-mates had to ply him with brandy and smother him in blankets to keep him warm by the pavilion fire.

He made 1,775 runs that summer at an average of 49.31. Wisden reported that “he scarcely ever looked back from his brilliant start, quickly became accustomed to the strange surroundings of county cricket and scored heavily against all classes of bowling. His wonderful placing on the leg side was quite disheartening for the leading professionals who were unaccustomed to seeing their best ball turned to the boundary for four.”

On the more benign pitches of the County Ground, where the short square boundaries encouraged high scoring, Ranji soon made himself at home. Crowds of up to 10,000, most of whom had never seen a black man before never mind one who was supposedly an Indian prince, flocked to the ground. Ranji loved Brighton. He took up residence at the Norfolk Hotel, only occasionally paid his bills, while the Royal Pavilion conjured up visions of India. He loved the town’s vitality and sense of style. Eastbourne? Forget it.

He started with 150 against MCC and four half-centuries which was followed a chanceless, unbeaten 137 to save the game on a broken wicket against Oxford University. Later in the season, on a pitch badly affected by rain, he scored 100 out of a total of 171 against Nottinghamshire while against Middlesex he shared his first century stand with Fry, 117 in 70 minutes.

His form did tail off towards the end of the season, as the mental and physical rigours of playing so often for the first time in his career as well as the expectancy to score runs, began to take their toll.

By the end of June 1896 he had already scored five hundreds, including an innings of 146 for MCC against a Cambridge University side whose attack was led by the formidable fast bowler Jessop and who described Ranji as “just about as perfect a specimen of batsmanship as one could desire.”

By then Ranji had enjoyed one of his first encounters with the touring Australians in a country-house match at Sheffield Park which attracted crowds of 50,000 including the Prince of Wales. Ranji made scores 79 and 42 on a difficult pitch and showed that he could cope with a sharp Australian attack led by Ernie Jones, who hit several players including Grace, but not Ranji (although he dismissed him 13 times, more than any other bowler in his career).

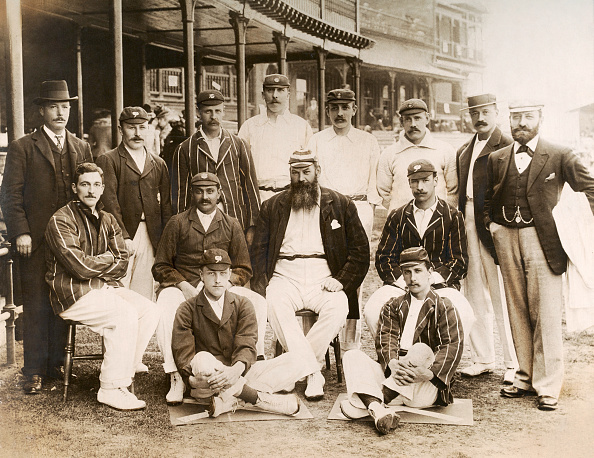

The South of England cricket team that played the touring Australia team at Eastbourne, England on 21st May 1896, including Ranjitsinhji (bottom centre)

The country-wide clamour for him to be chosen for the first Test at Lord’s on June 22 was growing but the MCC refused after much prevarication, its President Lord Harris claiming that Ranjitsinhji was not of British stock and would one day return to India. On the day the Test started a subdued Ranji was bowled by Jessop for his first duck in almost two years.

There was a public outcry about MCC’s decision but Ranji’s admirers didn’t have to wait long. In those days the county who were hosting the Test match picked the England team rather than a panel of selectors and while Ranji was playing for Sussex against Kent at Hastings he received a telegram from Old Trafford asking him to play. Ranji replied that he would, provided that the Australians had no objection, which they didn’t.

The crowds flocked to Old Trafford with 30,000 in attendance on the first morning but Australia, who had lost the first Test at Lord’s, dominated the opening two days. Despite a steady 62 by Ranji, batting at No.3 and one of five amateurs in England’s top seven, England followed on 181 behind. At stumps on the second day he was still there but his side was trailing by 72 runs with four wickets down.

Ranji was at his peerless best the following day. Despite being hit on the ear lobe by Jones, he progressed from 50 to his maiden Test hundred in just 45 minutes and finished with an unbeaten 154, having scored 17 of his 23 boundaries in the morning session. He had become the first batsman to score a Test hundred before lunch.

Australia lost seven wickets chasing their target of 125 but for the Manchester crowd the abiding memory was that of Ranji taking the Australian attack apart. The Guardian was effusive in its praise. “No man living has ever seen finer batting than Ranjitsinhji showed in this match. Grace has nothing to teach him as a batsman.”

Ranji, who was suffering from asthma – a complaint which dogged him throughout his life - and then trod on a carpet nail in his hotel room, was dismissed twice cheaply in the deciding Test at the Oval and was unable to take the field on the final day, when England bowled out Australia for 44 to clinch the series.

The England squad and Ranjitsinhji ahead of the first Test match vs. Australia

But with the spotlight, temporarily at least, off him Ranji returned to Brighton and began enjoying himself again. Batting at No.7 against Lancashire because of a finger injury, he single-handedly staved off defeat with a brilliant 165. Sussex’s next opponents were champions-elect Yorkshire when Ranji produced one of the best batting performances in the county’s history.

The game started on Thursday August 20 with Yorkshire making 407 and when rain intervened Sussex had responded with 23 for 2, Ranji batting at No.3 having not got off the mark.

On the Saturday morning a crowd of around 1,000 were there for the start although by the end it had grown by several thousand. In the first hour Ranji utterly dominated the Yorkshire attack. The Sussex Daily News’ correspondent wrote: “In his fine display the Prince, by superb wrist play and marvellous placing on the leg side, grand driving and crisp cutting, evoked the enthusiasm of his many admirers.”

The innings had resumed at 11.35 and immediately captain Murdoch was taken at slip off George Hirst, bowling from the sea end. This was a formidable Yorkshire attack, led by Hirst and also including Stanley Jackson and Bobby Peel, but Ranji showed them scant regard, bringing up his 50 in just 45 minutes.

He took 10 off one over from Jackson and 14 off Peel and with Billy Newham providing valuable support at the other end, they took the total past 100. With the score on 150, Hirst came back into the attack. The Sussex Daily News reported: “In his second over the Prince, with a trio to long-leg, secured his century to prolonged and deafening applause. He had been batting for an hour and a half.”

In the next over, Ernest Smith had Ranji caught at slip for exactly 100 with the total on 155. “On returning to the pavilion he was greeted with much enthusiasm,” added the Daily News. His innings had included 18 fours and evidence that he was batting on a different level to the rest of the Sussex team came with the dismissal of the last six wickets for just 36 runs.

All out for 191, Sussex began their second innings at 2.45pm on the final afternoon in arrears by 216. Fry and Billy Marlow, one of five amateurs in the Sussex team, batted cautiously and when Fry fell for 42 Ranji returned to the wicket for the second time in the day to more warm applause.

There was an early scare when he was nearly stumped off Brown but soon he began treating a crowd which had grown to around 3,000 to sumptuous stroke-play and the Yorkshire attack with utter disdain. Hawke used eight different bowlers in Sussex’s second innings and clearly it had become physically difficult for Hirst and Peel, who bowled more than 30 overs each in the day, to maintain their accuracy, although they remained economical.

By the time Marlow was out for 30 the second wicket pair had put on 72 and although there was a brief respite when Yorkshire bowled three successive maidens Ranji was soon back in full flow. “It is not often that the Yorkshire bowlers have been treated with so little respect,” reported Wisden. “His brilliancy and determination enabled Sussex to escape honourably from their position.”

Ranjitsinhji in Sussex colours

For the first time in the day, Ranji found a partner prepared to match him – or at least try to match him - stroke for stroke in Horsham’s Ernest Killick. They wiped off the first-innings deficit as Ranji moved into the 90s by which time an exasperated Lord Hawke had thrown the ball to David Denton, who played 11 Tests for England as a batsman but had no great pretensions as a bowler.

Ranji drove him to long leg for three to take his score to 99 and then took a quick single off Hirst in the next over to reach his century in five minutes shy of two hours at the crease. “The spectators cheered again and again and the Yorkshire team joined in the deafening applause,” wrote the Daily News.

The draw having been secured, the third wicket pair took their stand to 123 by stumps, Ranji driving the last ball of the match for four to finish on 125 not out.

“After the match a large crowd assembled in front of the pavilion shouting for ‘Ranji’ applauding continuously,” reported the Sussex Daily News. “The demonstration, which was of the most hearty character, was maintained for several minutes with the occupants of the pavilion joining in until the Prince was induced to come from the dressing room and acknowledge the applause.”

There are no other recorded instances of the same player scoring two hundreds on the same day of a first-class match. As Ranji achieved this 116 years ago it makes his performance even more astonishing, although he was a remarkable cricketer.

“He was an artist with an artist’s eye for the game,” observed CB Fry. “Ranji’s big innings pleased him in proportion as each stroke approached perfection. He tried to make every stroke he played a thing of beauty.”

Ranji made a total of 58 hundreds for Sussex as his legend with the country grew. He captained the side for five years between 1899 and 1903 but only played in three completed seasons after that in 1904, 1908 and 1912, passing 1,000 runs on each occasion. By then domestic responsibilities in India were taking up much more of his time, although he didn’t stop making an impression.

Arthur Gilligan, a future Sussex captain, remembers being taken to the Oval in 1908 to watch his hero, by now 35 and thickening somewhat around the waist, bat for the first time. “Sussex batted and after what seemed like an interminable period, Ranjitsinhji came down the steps to a storm of cheers and applause.

"I was thrilled to the core because the Jam Sahib was my hero. I can visualise him now: that elegant stance, the glorious late cut, the superb leg-glance, that lightning control of the bowling and that wonderful eye, which seemed to indicate that he could see the ball in its flight a fraction quicker than the average English player. What nectar of cricket it all was.”

After nearly 25 years of disputed succession, Ranji had returned to India and eventually succeeded onto the Nawanagar throne in 1907. He proved to be an imaginative ruler and played an important role in Indian affairs, twice representing his country at the League of Nations.

Ranjitsinhji (far right) on his second Sussex debut

He made a brief but misguided return to Sussex cricket in 1920 when he was persuaded to play three games despite being portly and out of breath. His real motive was to see how he might do without the use of his right eye which he had lost in a shooting accident on a Yorkshire moor in 1915.

Scores of 16, 9, 13 and 1 made it clear, as Wisden observed, that “whatever they had seen in the rotund figure of an Indian prince at the wicket it had not been Ranji.” He died of a heart attack in April 1933 at the age of 60.

Ranjitsinhji’s name is never far away from the pages of the Sussex record books. He made the highest score for the county against both Essex (230 in 1902) and Surrey (234* also in 1902) while no batsman in the county’s history has made more than his 14 double hundreds.

Only CB Fry (68) and John Langridge (76) made more centuries while his 1900 aggregate of 2,824 first-class runs has only been bettered by three players: Langridge, Jim Parks senior and Fry. He scored 1,000 runs eight times including 2,000 runs on four occasions while his partnership of 344 with Newham against Essex in 1902 is still a record for the seventh wicket in England.

He has been the subject of eight biographies; the best Simon Wilde’s exhaustively researched and acclaimed study in 1990 which was shortlisted for the Sports Book of the Year award. In it, Wilde worked diligently to uncover much more about him than his prowess on the cricket field.

Away from cricket, Ranji was by no means perfect. Until he became the Jam Sahib in 1907, he was notoriously impecunious but spent lavishly and left a string of bad debts. And, of course, when he arrived for the first time in England in 1888 his claims to princely status were tenuous to say the least.

Adopted as an heir by the Jam Sahib against the ruler’s failure to father one of his own, his princedom was revoked four years later and not restored for another 25 years.

But when the Victorian Age became the Edwardian Age he was the most celebrated cricketer and arguably the most celebrated sportsman in the world, notwithstanding the pre-eminence of WG Grace.

“It was the age of simple first principles, of the stout respectability of the straight bat and good-length balls,” wrote Neville Cardus. “And then suddenly this visitation of supple, dusky legerdemain happened. A man who played as no one else in England could possibly have played. The honest length ball was not met by the honest straight bat but with a flick of the wrist charmed away to the boundary.”

Above all else, though, he is still remembered as one of cricket’s first superstars and for a record that is unlikely ever to be repeated in the history of the game.

This piece originally featured in Bruce Talbot's fantastic book, Sussex CCC Match of My Life. Bruce has also worked with former Sussex captain Ian Gould on his autobiography, Gunner, which is out now and published by Pitch (£19.99).